Ink and Tears: Murdering a Fictional Friend

Ink and Tears: Murdering a Fictional Friend

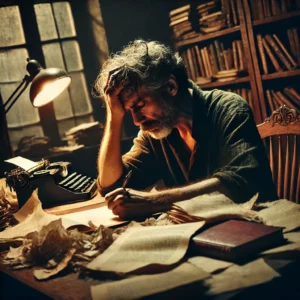

As a fiction writer, my journey through the realms of storytelling has been nothing short of thrilling. The ability to create entire worlds, breathe life into characters, and guide their destinies is a humbling power. Yet, a dark and harrowing facet of this craft plunges me into a pool of anguish and torment—the act of killing off characters that I have come to love.

Does that sound weird? When I wrote the first draft of this post, I shared it with my wife. She looked at me horror-stricken (and no, I am not being dramatic) and asked me not to post it for fear you all might just think I was crazy. Indeed, I don’t really love my characters. I don’t really feel anguish and torment when I have killed one. Or. . . do I?

I admit I had to stop and consider whether I felt those things. Turns out I do. So, I turned to Google, which we all know is never wrong 😉. Yet, it only took about a minute of research to find that most authors anguish as I do. So, why did my wife find it weird?

Plotter or Pantser?

To answer that, I need to explain what type of writer I am. Most writers fall into one of two categories—plotters or pantsers. Plotters are pretty apparent in meaning. These authors plot out their books in great detail. They know virtually everything that will happen before they even start writing. I have read that John Irving falls into this category. Pantsers, on the other hand, often have no idea what their book is about when they start writing. The term comes from the writing by the seat of their pants. (I will dig deeper into this in another blog post). Stephen King is a pantser. In fact, he seems to be offended that plotters even exist (picture him making gagging sounds at the thought of plotting a novel).

I, my friends am a pantser. Stories don’t come to me. Characters do. And once I meet them, they take up residency in my head. They talk to me and share their story. I write it down. At the time of writing this post, I have just completed the first draft of my current work, The Last Sundancer. I met Jess, the last Sundancer, about two years ago. He hung out with me while I finished the Trinitarian Knights Collection. We weren’t alone. Moo and Ahke hung out with us as well. Who are Moo and Ahke? Other characters for other books. Jess was ready to tell his story. The others, not as much. So Jess’ evolution has grown from mind to page.

Now, a statement like that is another that definitely raises an eyebrow of my wife. That’s ok. It’s my process. And my process makes my characters real to me. Yet, I have still thought much about these characters’ emotional impact on me.

Robert Frost said, “No surprise in the writer, no surprise in the reader. No tears for the author, no tears for the reader.”

Man, I love that quote. Probably just because it allows me to feel sane in my process.

As a pantser, I don’t know what my characters will do in many situations. I am often told that it is silly. I am the author, and I tell them what to do. Yet, writing, I think, has some similarities to acting. An actor can spend months learning to get inside their characters’ heads. The truth is that the best acting may not actually be acting at all. Maybe the actor is so far into character that we are just watching that character live. I have been listening to an audiobook about Nicholas Cage. He goes deep into character before filming even starts. He has even traveled as that character and lived as them to become them. I bet his academy award looks damn good on his mantle.

As a writer, I have to get into the heads of each of my characters. I must let part of my mind become them and then listen to them. And when I think I know where my story is headed, SURPRISE! A character does something I didn’t expect. And that, my friends, is the surprise Robert Frost is talking about.

In the delicate tapestry of storytelling, my characters are the threads that weave the tapestry of narrative together. Each character possesses a unique personality interwoven with elements of mine, a soul with tiny traces of me sprinkled throughout, and a purpose within the story’s grand design. They are my companions through countless nights (often waking me up to talk), my confidants as I traverse the landscapes of imagination, and the flashlight holder when I peer into the dark recesses of my mind that I fear exploring. And when the time comes to let one of them go, it’s a decision that leaves me grappling with emotions that mirror those of the characters I’ve created.

Questions torment me as they perish. Did I tell their story as they wished? Was their death purposeful? As a reader, will you anguish over their loss as I do? Or, when I have murderer’s remorse, should I find a magical way to bring them back to life?

The Grief of Loss

As a fiction writer, I grieve alongside my readers, for I am the first to feel the loss. I witness the final breath often in fifty ways that a reader never sees, the last whispered words, and the extinguishing of a fictional soul. It’s a peculiar brand of grief, for I mourn the death of something that never truly lived yet had an existence in my mind and heart. And while a reader may spend a few weeks with a character, I may have spent a few years (or even a decade) with them as their story unfolded in my mind.

No one finds it strange that a reader cries when reading a book. It is often expected. Many people who read books multiple times cry each time. So, why wouldn’t the writer? For a reader to read the four books in the Trinitarian Knights Collection that I wrote, they likely invest about twenty-five hours of their time into my characters. Yet, I have received letters from readers saying they have cried, laughed out loud, and sat in silent reflection at different times in my books. Yet, those particular characters spent ten years in my head. Saying goodbye to them was hard. After ten years, why wouldn’t I feel the emotions readers feel at an even greater level.

The Emotional Release of Closure

Despite the anguish, there is an unseen benefit. The death of a character is a catalyst for growth and transformation, both within the narrative and for me as a writer. It forces me to grapple with themes of mortality, sacrifice, and the impermanence of life. It’s a reminder of my mortality and the fleeting nature of existence.

The death of a character can lead to some of the most emotionally charged and resonant moments in a story. It can evoke empathy, elicit tears, and ultimately deepen the reader’s and the narrative’s connection. It’s the emotional release that arises from facing the inherent tragedy of life head-on.

In Conclusion

As a fiction writer, killing off a character is a rite of passage that brings forth a torrent of emotions, from sorrow and guilt to catharsis and closure. It’s a reflection of the human condition, a reminder of the transient nature of existence, and a testament to the power of storytelling.

So, I continue to write, knowing that within the depths of my narrative, characters will be born, live, and inevitably, some will meet their end. It’s a bittersweet dance of creation and destruction, reminding me that every ending is also a new beginning in the world of fiction.